The A-10 Warthog, officially the Thunderbolt II, is an aircraft unlike any other in the US Air Force fleet. With its iconic GAU-8 cannon, rugged airframe, and unmatched record in close air support (CAS), it has become a legend among ground troops and a symbol of battlefield toughness.

But now, the A-10 era is coming to an end. The USAF began retiring the fleet in 2023, with full withdrawal expected by the early 2030s. Its departure has reignited a fierce debate over what, if anything, can truly take its place.

The Warthog’s long career has also spawned plenty of myths: some rooted in outdated facts, others in fan devotion. In this article, we separate truth from fiction, busting ten of the most common misconceptions about the A-10, from its design philosophy to its survivability, and its role in tomorrow’s Air Force.

1. The A-10 Warthog was designed entirely around its gun

One of the most persistent myths is that the A-10 Thunderbolt II was built solely to accommodate the monstrous GAU-8 Avenger cannon. While the gun was a centerpiece of the design brief, the aircraft wasn’t entirely built around it.

The USAF’s 1966 AX (Attack Experimental) program emphasized survivability, long loiter time, and short-field performance, key characteristics for close air support (CAS).

The idea of attacking armored targets at close proximity to friendly troops was at the core of the program when it was being envisioned, and the Requirements Action Directive, which set the A-X program in motion in 1966, already included internally mounted guns with firepower equal or greater than four 20 mm M-39 canons.

However, that was not the only requirement and, along with the CAS role, the A-X had to perform other kinds of ground attack. The request for proposals USAF issued in 1970 did not even include a gun, but required the aircraft to carry at least 9,500 lb (4,309 kg) of ordinance.

The GAU-8 was integrated early on, and Fairchild Republic’s winning design did revolve around its placement and recoil forces, but it also had to withstand ground fire, operate from austere runways, and remain airborne long enough to support troops in prolonged battles.

While a gun (or at least a recoilless rifle) was always in mind during the design of the jet, at no point was it envisioned as its only armament. The USAF simply needed an attack jet which could do everything earlier attack aircraft did, but better. Carrying a massive gun was just one of the ways to fulfill that objective, and the GAU-8 was just one of the candidates for that position as the aircraft was being designed.

The “gun-first” narrative is popular in documentaries and forums, but as Air Force historian Dr. Richard Hallion has noted, the A-10 was “an integrated CAS system,” not just a flying gun.

Indeed, as Mike Scanlon, an A-10 Crew Chief, told Simple Flying, “Perhaps when the A-10 was designed, the gun seemed like a great idea, but as missile technology improved and A-10 pilots became more comfortable using them, missiles became the primary weapon of choice.”

2. The A-10 is too slow and weak to survive modern combat

It’s true that the A-10 Warthog isn’t fast. It cruises at around 300 knots, but its mission doesn’t demand speed. Instead, the aircraft is built to fly low and slow, giving pilots time to visually identify targets and respond quickly to calls from troops on the ground.

Critics argue this makes the aircraft vulnerable, particularly in high-threat environments, and cite the growing reach of modern surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) as evidence that the A-10 can no longer survive on the battlefield.

But this ignores the jet’s extensive countermeasures, ability to operate below radar coverage, and battle-proven ruggedness. During Operation Desert Storm, A-10s flew over 8,000 sorties, downed two helicopters, and returned home with significant battle damage that would have downed other jets.

There are also arguments that the GAU-8 is ineffective against modern tanks. When designed in the 1960s, the GAU-8 and its 30×173mm PGU-14/B armor-piercing projectile with depleted uranium core were more than sufficient to penetrate the side and rear armor of the majority of Soviet tanks.

On paper, it can punch through 55 millimeters of rolled steel when fired from 1,200 meters and up to 76 millimeters when fired from 300 meters at a 30-degree angle. Better penetration could be achieved at steeper angles, and at shallower angles, the penetration is much smaller.

The front, side and turret armor of most modern tanks is much thicker than that. Modern Soviet and Russian tanks, such as the T-64, the T-72, the T-80, the T-90 and their variants, have a minimum of 60 mm of steel armor on their sides and back. Western and Chinese tanks of the same generation have roughly similar levels of protection.

However, nearly all modern tanks also sport composite armor – additional layers of protection such as the steel-aluminum-steel sandwich of the T-72A or something more high-tech on Western vehicles. Furthermore, ERA covers the most vulnerable areas of modern tanks, and while older types of such armor are only effective against high-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) rounds, the latter ones were designed specifically with kinetic penetrators in mind.

Despite all this protection, several vulnerable areas remain, such as the lower side plates between the tank’s rollers (wheels) on the tanks without side skirts. Furthermore, with the GAU-8 spraying 70 shells per second, multiple hits on the same spot may appear possible.

During a 1979 USAF test, in conditions that simulated hostile airspace, an A-10 attacked a formation of ten M47 Patton tanks, firing 174 rounds in short bursts at an average range of 753 meters (2,470 feet). Some 90 rounds hit the tanks, but only 30 of them penetrated the armor. Three tanks were destroyed, four more immobilized, and three of those sustained damage to their weapons systems.

The dispersion of rounds, the speed of the aircraft and a need to evade anti-aircraft fire make sustained fire on one target, which would increase the probability of hitting vulnerable areas, nearly impossible. In the best of circumstances, the A-10 can fire just a short burst at one target before having to disengage, which is precisely the reason its gun was designed with such an extreme rate of fire in mind.

Hence, modern main battle tanks are practically invulnerable to the GAU-8. However, as stated above, other kinds of armored vehicles are still vulnerable. For example, the BMP-3 – the newest Russian infantry fighting vehicle – has just 35 mm of armored plating at most, and can be defeated by the GAU-8 even from the front.

So, does GAU-8’s inability to defeat modern tanks mean that the A-10 and its gun are useless? Absolutely not.

First off, the aircraft can carry an array of other weapons, such as precision-guided bombs and missiles, that can rip modern tanks to pieces.

Most importantly, MBTs are far from being the only viable targets for the A-10. Armored personnel carriers (APCs), infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs) and other kinds of military hardware have much less armor than tanks and can be penetrated by high-explosive shells of the A-10. Unarmored targets, such as supply trucks, are even more vulnerable.

So, while the GAU-8 lost its anti-tank potential decades ago, it remains an effective weapon against a lot of battlefield targets.

3. The A-10 is outdated and on its last legs

The idea that the A-10 Warthog is an obsolete Cold War relic has gained traction in recent years, especially as the US Air Force pushes to retire the fleet. However, “outdated” is a relative term.

The A-10C upgrade program, completed in the 2010s, gave the Warthog a glass cockpit, modern targeting pods, digital comms, JDAM compatibility, and advanced situational awareness. Many of its analog systems were replaced, extending its operational relevance into the 2020s.

The upgraded A-10C has proven capable in a range of environments thanks to its advanced targeting pods, such as the Sniper XR and Litening ATP. As well as this, the aircraft received a glass cockpit, data link integration and night vision goggles for pilots. This upgrade brought the A-10 into the digital battlespace, enabling operators to do things they could never have dreamed of in the original A-10 Warthog.

These systems provide high-resolution infrared imagery, laser designation, and GPS-guided targeting, enabling precision strike capability even in poor visibility. As a result, A-10s have conducted effective missions in Iraq and Afghanistan at night and in dust storms, scenarios where precision and persistence matter most.

In a further update in 2022, the USAF added new and improved wings to the A-10 Warthog, giving more durability and a boost to the flying time of the aircraft.

Nonetheless, in 2023, the USAF began retiring A-10s as part of a broader force restructuring. Critics of the aircraft, including senior Air Force leadership, argue that modern threats require multi-role, survivable platforms like the F-35. Proponents, however, including lawmakers and former A-10 pilots, argue that no other aircraft provides the same level of persistent, responsive, and close-in fire support.

Arguments have also been made for the A-10 having extreme vulnerability to man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS). Six A-10s were lost in combat, three of them shot down by MANPADS and three more by vehicle-mounted infrared-guided missiles during the operation Desert Storm in 1991, according to the official report of USAF combat losses. An official evaluation of the campaign by the US military shows that three more A-10s were damaged by heat-seeking missiles but managed to return to base, while 11 more were heavily damaged by other kinds of anti-aircraft fire.

However, probably the best-known example of the A-10 surviving a MANPADS hit comes from the Iraq war of 2005, when the A-10 piloted by Captain Kim Campbell was heavily damaged over Baghdad, but still returned to base. This survivability is unmatched in any contemporary platform, and saved countless lives during operations in the late 20th century.

4. The A-10 Warthog strafes targets in a line

If you’ve watched a film featuring the Warthog or played a video game, this is typically how the jet is portrayed. As the A-10 flies above the target, the area in front and below the aircraft lights up with hundreds of small explosions, one slightly in front of another, in a trail of destruction.

Can combat aircraft strafe targets in a line? Absolutely. A tactic of firing guns in a gentle dive, while slowly transitioning to a level flight, is something that aircraft have done since WWI. It allows the engagement of multiple targets at once, with devastating effects on columns or larger formations.

Is this how A-10s typically attack their targets? No. The vibration of the GAU-8 is very powerful and can throw the pilot’s aim off, so, a special system locks the aircraft’s controls as soon as the trigger is pressed. Hence, all the videos portraying A-10’s performing an actual attack show the aircraft aiming at one particular spot, firing, and then switching onto another target.

But in films, A-10 attacks always look different. From serious war dramas to cheesy blockbusters, many Hollywood movies that feature the A-10 include the cliché of the A-10 strafing targets in a line.

The system that prevents the aircraft from doing so is called Precision Attitude Control (PAC): a rudimentary autopilot that takes over the control of the aircraft as soon as the pilot pulls the trigger. It is just one of a variety of systems designed to protect the aircraft from the adverse effects of its giant gun.

Truth be told, PAC can be switched off by the pilot. That would allow the A-10 to strafe targets in a line, just like the ground attack aircraft from WWII. However, not only would that be counterproductive, but it could also put the jet and its pilot in danger. And so, videos that show the A-10 firing its gun in combat or training feature an attack on one target, with the PAC system turned on.

A similar myth exists that says the A-10 was designed to strafe tanks from above, targeting their weaker top armor. While this is possible, it would be dangerous to undertake and not the primary way the A-10 is intended to be used.

A-10 pilots were trained to fly low and attack the sides and the rear of tanks, without resorting to trying to punch through the roof of a tank. Such an attack profile was imperative to avoid being shot down by anti-aircraft fire, and fairly effective against Soviet tanks of the time.

In addition, the speed of the A-10 makes attacking in a dive highly impractical – much faster than WWII-era bombers, the Warthog was simply not designed for that.

Strafing the target from its side, in nearly-level flight, was always the intended use of the GAU-8. Its ammunition was developed to penetrate the side armor of the T-62 tank, and the targeting system was designed with such a use in mind. In fact, a lot of testing was conducted to fine-tune such aspects as the angle at which the gun is mounted.

As the development documentation shows, attacks with dive angles of 50 to 70 degrees were also considered. But they were intended for dropping unguided bombs, not strafing.

The ideal angle for the gun run was considered to be less than six degrees. There are multiple reasons for that. First of all, even at the minimum speed of 200-300 knots (370-550 kilometers per hour) the window of opportunity for firing the weapon is too small. In addition, the Soviet-armored formations – the prime target for the GAU-8 – always had ample air defenses, and the slow dive in a straight line would make the aircraft too vulnerable.

As a result, A-10 pilots during the Cold War were trained to fire at the sides and the rear of tanks.

5. The A-10 Warthog can’t survive if hit or damaged

The Warthog’s reputation for battlefield toughness is well-earned. One of the most famous examples is that of previously mentioned Capt. Kim Campbell, who flew her A-10 back to base in 2003 after taking heavy anti-aircraft fire over Baghdad, losing all hydraulics and operating the jet manually.

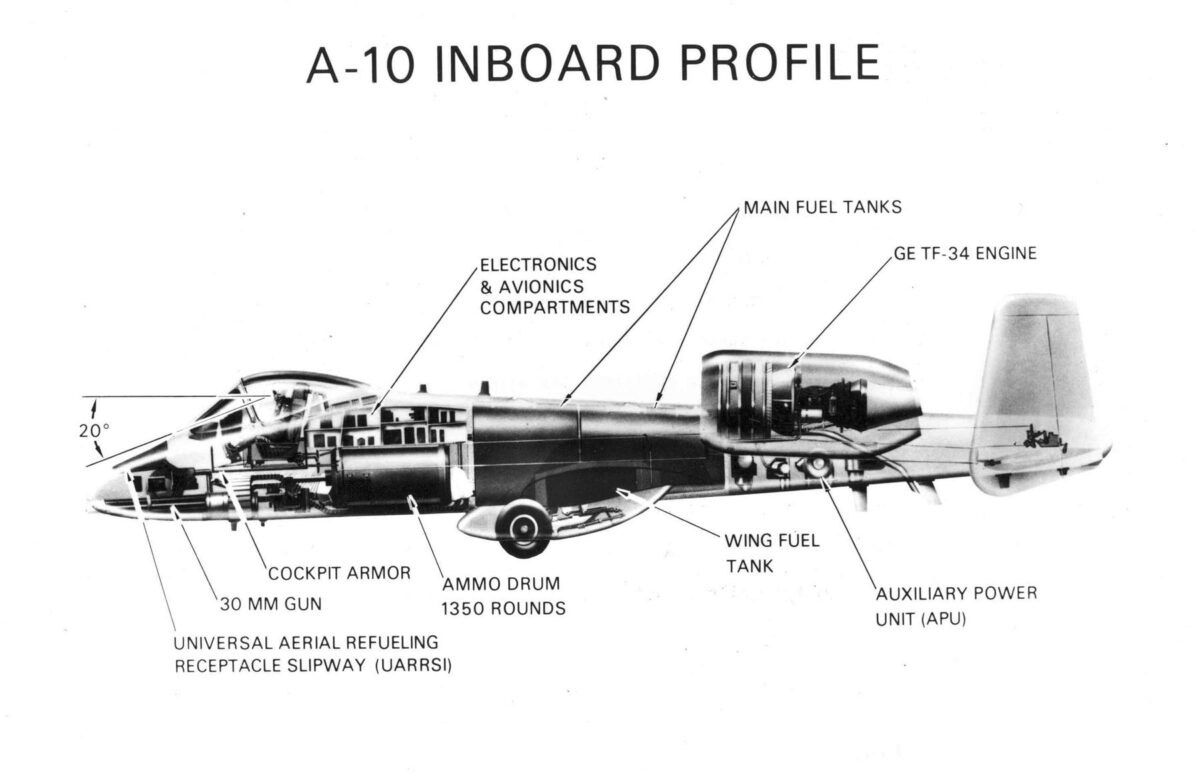

The aircraft’s redundant systems, titanium “bathtub” armor around the cockpit, self-sealing fuel tanks, and separated control lines all contribute to its survivability. In Afghanistan and Iraq, multiple A-10s returned to base with severe wing and fuselage damage.

Many modern jets are designed with stealth or standoff capability in mind, not with the same emphasis on absorbing punishment. As former A-10 pilot Lt. Col. Ryan Haden, 23rd Fighter Group Deputy, Moody AFB, told Warrior in an interview,

“The A-10 is not agile, nimble, fast or quick. It’s deliberate, measured, hefty, impactful, calculated and sound. There’s nothing flimsy or fragile about the way it is constructed or about the way that it flies… It is built to withstand more damage than any other frame that I know of.”

However, the effectiveness of the ‘titanium bathtub’ is often overstated too. It is essentially a box, bolted together from metal sheets between 0.5 in (12.5 mm) and 1.5 in (38 mm) in thickness. It was designed to reliably protect the pilot and aircraft controls from small arms fire and fragments coming from below. Contrary to popular belief, the A-10’s canopy (the glass top of its cockpit) is not armored.

So, while the A-10 is quite heavily armored for an aircraft, the qualities of its armor are sometimes exaggerated by its fans. Nevertheless, in active combat, it has proven itself to be a valuable protector of Air Force pilots.

Recalling his experience piloting an A-10 during Desert Storm in 1992, Col. Bob Efferson shared with the Cradle of Aviation Museum that, “If it hadn’t been for the titanium bathtub, I probably wouldn’t be here. The right side below the cockpit had seventeen major holes in it and the bathtub had a lot of chinks in it. Think of that; seventeen major holes just below the cockpit and I didn’t get a scratch! It has to be a rugged airplane to sustain that kind of damage.”

6. The A-10 is less cost-effective than modern multi-role jets

This is a classic false equivalency. Critics argue that the A-10 is a “single-mission” aircraft and therefore not worth maintaining in a modern force structure focused on versatility. But when it comes to delivering close air support, few platforms are as efficient.

According to USAF data, the A-10 costs around $20,000 per flight hour, significantly less than the F-35A, which can exceed $36,000. The A-10 is also easier to maintain in the field, thanks to its modular parts and rugged construction.

The argument gets murkier when factoring in sustainment costs for aging airframes and infrastructure, but as RAND analysts have pointed out, CAS effectiveness can’t be measured purely in dollar signs. The question is not just what you pay, but what you get for it, and in permissive airspace, the A-10 remains a low-cost, high-impact option.

Indeed, in a report titled ‘Thunder versus Lightning,’ the Belfer Center concluded that, “The proposal to replace the A-10 fleet with Joint Strike Fighters is operationally and fiscally unsound, and would seriously harm US national interests. In a future where budgets are tight and low-intensity conflicts requiring precision CAS are likely, a cost-effective US air fleet must include the A-10 Warthog.”

7. The A-10 was the first armored aircraft

The A-10 Warthog is often portrayed as having armor that is an outstanding innovation and a feat of ingenuity. The truth is that the A-10 wasn’t the first aircraft to use this kind of feature. The history of armored aircraft stretches back to WWI, and the Warthog is just another iteration of the concept, which was successfully implemented before.

For one, the A-10 was conceived as a replacement for the A-1 Skyraider, which featured an impressive collection of armor plates around the nose. They were not joined into a single structure, yet protected both the pilot and certain parts of the engine.

However, the best-known armored aircraft – as well as the inspiration for the A-10‘s protective system, as its development documentation indicates – was the Ilyushin Il-2 Shturmovik, a WWII-era Soviet ground attack plane. Its armored bathtub, made of steel, covered an entire center-section of the plane and protected the crew, engine, avionics and fuel tanks.

Was the Il-2 the first armored aircraft? Not even close. As far back as WWI, various countries had begun experimenting with armoring their aircraft, and although those biplanes and triplanes were not exactly powerful by today’s standards, the armored bathtub has roots in that era.

The German Junkers J.1, which entered service in 1917, is often credited as the world’s first armored aircraft and features a steel bathtub similar to the one later seen on the A-10. Of course, it was only 5 millimeters thick and barely enough to stop a rifle round, but the trend had to start somewhere.

8. The A-10 is incompatible with modern warfare

This myth lingers from the aircraft’s early days, when it lacked the data links and comms needed for dynamic, joint operations. But today’s A-10C variant features Link 16, SADL (Situational Awareness Data Link), secure radios, and digital threat displays, enabling it to integrate with drones, forward air controllers, and fast jets in real time.

A-10s also carry the same advanced targeting pods used by F-16s and F-15Es. They’re regularly deployed alongside allied forces in NATO operations and have demonstrated joint interoperability in campaigns like Inherent Resolve and Atlantic Resolve.

In a 2022 exercise, A-10s were employed to carry ADM-160 Miniature Air-Launched Decoys (MALDs) to simulate and confuse enemy air defenses. This operation showcased the A-10’s capability to support 5th-generation fighters like the F-35 and F-22 by acting as a decoy platform. Capt. Coleen Berryhill, an A-10 pilot, remarked: “We are building on our old principles to transform into the A-10 community the joint force needs.”

From its very inception, the A-10 was designed to take off from unpaved and damaged airstrips near the front line. It can launch from runways as short as 3,000 feet and doesn’t require pristine concrete.

Its wide-set landing gear, low landing speed, and powerful brakes allow it to operate from highways, dried lake beds, and improvised forward bases—capabilities demonstrated in NATO exercises and real-world contingencies.

In Europe, this has become increasingly relevant again: the A-10 regularly participates in Agile Combat Employment (ACE) drills, which simulate dispersed operations under threat.

As reported by The Aviationist, A-10s from the 104th Fighter Squadron, Maryland Air National Guard, conducted landings on an unimproved dirt runway at Mud Lake on the Nevada Test and Training Range. This exercise demonstrated the A-10’s capability to operate in environments lacking traditional airfield infrastructure.

9. Pierre Sprey designed the A-10

Pierre Sprey was an engineer who was part of an arguably influential lobbying group, known as the ‘Fighter mafia’ or ‘the Reformers.’ According to memoirs of Sprey’s comrades, he designed every fighter jet the US built between the 1960s and the 1990s.

The truth is, he did not. Despite appearing in countless documentaries that credit him with working on the F-15, the F-16, the A-10 and other jets, Sprey never worked at Fairchild Republic, McDonnell Douglas or General Dynamics, the companies that created the jets he supposedly designed. The Fighter mafia contributed to the creation of the 4th generation of fighter jets, but the extent of that influence is also heavily debated.

The A-10 was actually designed by Alexander Kartveli, one of Fairchild Republic’s most prolific engineers. Fighter mafia’s and Sprey’s role in the design is highly debatable and can be described as ‘influence’ at best. And while Sprey was one of the staunchest and most vocal proponents of the A-10 in later years, he did not design the plane.

There are several reasons behind this bone of contention. For one, according to some claims, the Fighter mafia, together with Pierre Sprey, was instrumental in formulating requirements that led to the creation of the A-10. Supposedly, they were the ones to come up with the idea of an anti-tank aircraft with a gun as its primary armament.

Many of the experts who wrote books on the issue – including David R. Jacques and Peter C. Smith – disagree with this. According to them, the birth of the A-10 was not as straightforward, with many influences from various groups, primarily within the US Army and the Air Force, shifting and overlapping in a clash between doctrines. Also, the GAU-8 was never considered as the primary armament of the A-10 – the gun was just one of many requirements that were put forward.

Additionally, many events that the proponents of the Fighter mafia display as evidence of the group’s influence happened in the mid-1970s, when the A-10 was already designed and flying. This suggests that Sprey’s contribution to the project probably came too late to make any difference.

There is another claim: that of the influence of the Blitzfighter – a concept aircraft designed by the Fighter mafia’s James G. Burton – on the A-10. The bears an uncanny resemblance to the Warthog, with a 30 mm cannon in the nose, and an emphasis on survivability.

There is just one problem: contrary to many claims, the A-10 appeared earlier than the Blitzfighter, and not vice versa. As Burton himself admits in his book, ‘The Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old Guard’, he only started working on the concept in 1978, and proposed his design as a replacement for the A-10 which he saw as too expensive, too complex and too reliant on technology.

Somehow, in the minds of the Fighter mafia’s supporters, the chronology of the events was flipped, and the Blitzfighter was presented as the forerunner to the A-10.

10. The A-10 is no longer needed; drones and F-35s can do the job

This is arguably the most contested point in the CAS debate. Proponents of divestment argue that MQ-9 Reapers, AC-130 gunships, and F-35s can now fill the A-10’s role. But while these platforms offer high-end capabilities, none can fully replicate the A-10’s low-speed loitering, visual target acquisition, or ability to absorb battle damage.

A 2018 Air Force comparative test between the A-10 and F-35 showed that even in permissive environments, the F-35 struggled to match the A-10’s accuracy and responsiveness in live CAS trials. More importantly, troops on the ground consistently report a high level of confidence when A-10s are overhead, something no drone can yet replace.

In an interview with Business Insider, a US Air Force A-10 pilot identified as McGraw shared his experience in Afghanistan, saying, “Lot of times [when] we’re overhead, they’ll just put their guns down and go away because they know the A-10 is overhead.”

The A-10 may not be “irreplaceable” forever, but nothing fully matches its unique blend of survivability, simplicity, and surgical firepower. Efforts to replace it with light attack aircraft, armed drones, or stealth jets have each fallen short in at least one key area, be it endurance, firepower, or real-time coordination.

That said, the US Air Force has begun retiring the A-10 fleet as of 2023, with plans to phase it out entirely by the early 2030s. Whether anything fully replaces it, or if CAS doctrine adapts in its absence, remains to be seen. What’s clear is that the aircraft earned its loyal following not just from fans, but from the troops it protected.

A comprehensive analysis by the Project On Government Oversight (POGO) emphasized the A-10’s unparalleled effectiveness in close air support roles. The report stated: “Until a dedicated attack aircraft program can take over, the A-10 remains the best available tool to support the troops.”

What’s the future for the A-10 Warthog?

The A-10 Warthog may not be invincible, but its impact is undeniable. For decades, it delivered close air support with a mix of precision, durability, and presence that no other platform has quite matched.

While its retirement is now underway, the questions it raises about what airpower looks like at the lowest altitudes, closest to the fight, will echo long after the last Warthog lands. Whatever replaces it will have big titanium boots to fill.

As the US Air Force looks to the future, the Warthog’s legacy reminds us that combat effectiveness isn’t always about speed or stealth; sometimes, it’s about staying in the fight when others can’t.