Aloft on a near-perfect Sunday morning my ForeFlight screen suddenly came alive with a dozen green traffic triangles converging on Lee County Airport-Butters Field (52J) in Bishopville, South Carolina.

We were all inbound for a meeting of the South Carolina Breakfast Club.

The Breakfast Club, now celebrating its 87th year, calls itself the largest flying club of its type in the U.S., and one of the oldest.

Since 1938 aviators have regularly traveled on Sunday mornings (except during World War II) to breakfast fly-ins all over the Palmetto State and occasionally Georgia and North Carolina. The club usually meets once every two weeks with the designated fly-in airport set on the club’s calendar on its website.

“In the Breakfast Club, there are no bylaws and no dues,” explained Club President Stoney Truett. “The one rule is to fly safe. And if you attend once, you are a member for life.”

The Bishopville turnout of about 20 aircraft on Palm Sunday was relatively low by club standards. Some Sundays more than 100 aircraft fly in from all over the state and attendance has topped 400 individuals, according to club officials.

The formation of the Breakfast Club dates to 1938 when Orangeburg, S.C., jeweler Thomas Summers, an Ercoupe pilot, began taking his daughter for a flight on Sunday morning before church. There was a halt during World War II because of gasoline rationing, but the club resumed fly-ins after the war.

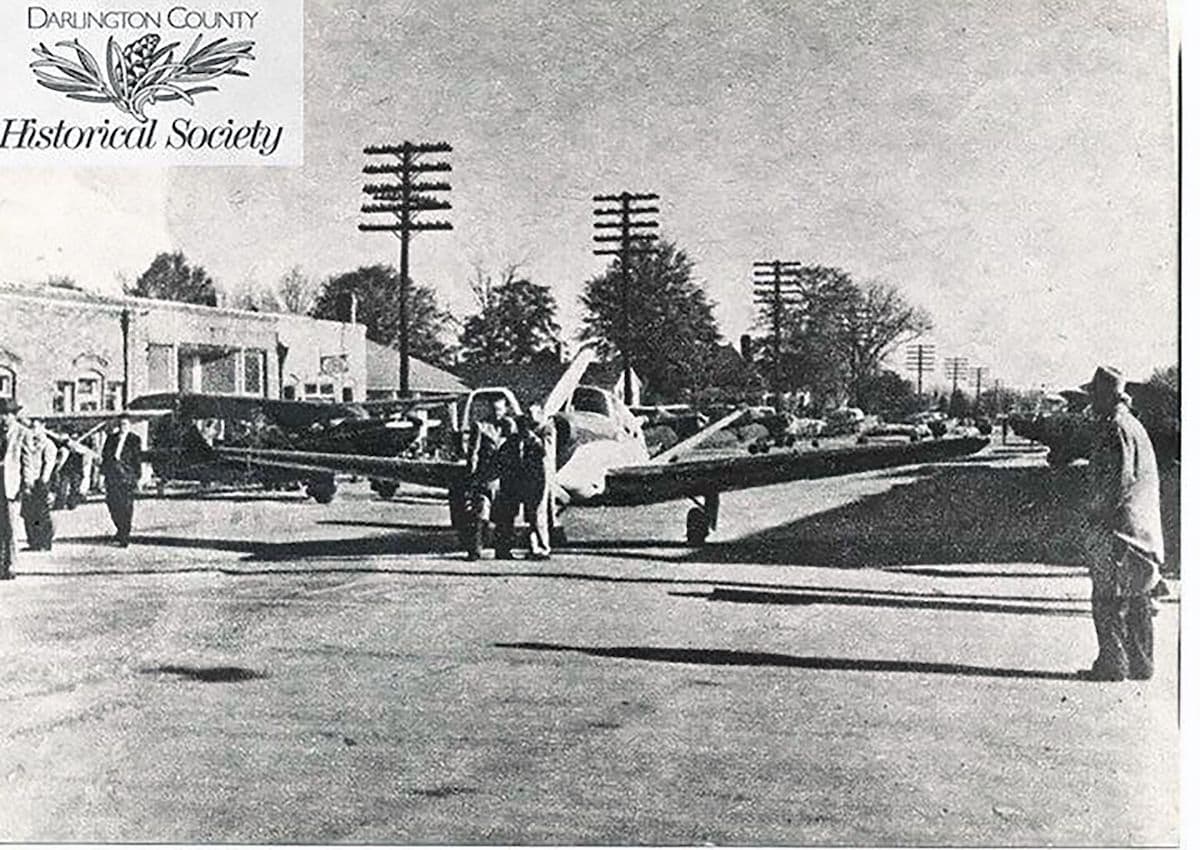

According to Truett, a highlight of that early post-war period was in July of 1946 when the meeting was held on Hunting Island Beach in Beaufort County. Another memorable fly-in on Jan. 4, 1953, included landings by 25 aircraft on main street in the Pee Dee town of Lamar.

For the breakfast I attended, I tucked my Skywagon into an airborne queue of seven aircraft two miles out from 52J.

Our arrivals were orderly and a crew of marshalers quickly got us parked. Moments later several cars rolled through the airport gate and lined up to shuttle new arrivals to downtown Bishopville, two miles distant.

The lead driver was airport manager George Roberts, a former U.S. Air Force Air Traffic Controller. Another car was driven by Linda Butters, widow of decorated World War II bomber pilot Ray Butters, for whom the field is named.

Bishopville, a town of about 3,000, is known for its South Carolina Cotton Museum and County Veterans Museum. It also celebrates legendary 1945 Heisman Trophy winner, Felix “Doc” Blanchard, whose father was once the town physician.

A hearty breakfast is the standard opening for a club meeting. It usually includes eggs plus grits and sausage or some variation in all-you-can-eat portions.

New flying friendships are a hallmark of every breakfast.

And the group is always as diverse as the aircraft attending.

On this day everyone from airline pilots to novice aviators arrived in a variety of planes that included a Travel Air, RVs, several 182s, Piper Archers, a J-3 Cub, a Sling TSI, and a Beechcraft Bonanza. They came from all over the state, from Greenville in the northwest to Myrtle Beach on the Atlantic. Two aircraft flew over from North Carolina.

After the meal Truett, a longtime flight instructor from Columbia, the state capital, welcomed attendees. Truett, a member of the South Carolina Aviation Hall of Fame, is a 40-year-plus veteran of the club.

His wife, Valerie Anderson, is the club videographer, and she was busy at work that morning filming for a YouTube post that would go online within hours. They arrived in their specially-equipped photo ship, a Rans S-6S with five cameras mounted on and in the aircraft.

Club Vice President Scott Crosby, who flew from Greenville in his 182 Skylane, also greeted newcomers.

Truett then called for the pilot who had flown the longest distance to the event. That flier is usually awarded a lifetime member hat.

However, he said he was altering tradition to present the hats to Bree Grant and Dean Price. Both are students finishing their Airframe and Powerplant course this year at the Pittsburgh Institute of Aeronautics Myrtle Beach campus. They arrived from Marion County Regional Airport (KMAO) in a Cessna 182 flown by Bree’s father Steven Grant.

The pilot judged to have made the most substandard landing usually gets to sign the bouncing ball Truett carries to every fly-in.

Apparently, everyone passed that test at Bishopville because no signature was added.

Pilots have been known to arrive extra early to avoid the bad landing recognition.

For the rest, arrivals are mostly in the 8 a.m. to 8:30 time slot and breakfast begins at 9.

The last formal event at the club meeting is a drawing with a single ticket holder taking the entire pot collected from all the pilots attending. One of the North Carolina pilots won the Sunday I attended.

These days, the fly-ins average two a month, occasionally three. The single out-of-state club meeting this year will be June 29 at Mid-Carolina Regional Airport (KRUQ) in Salisbury, N.C.

Meetings tend to break up spontaneously after about two hours. That was the case in Bishopville and the shuttle drivers were ready. A few minutes later props were spinning all over the parking area.

Anderson, the videographer, faithfully recorded each departure. A few hours later her photographic report was online.

“The club remains popular with pilots for the same reason you want to go for a $100 hamburger,” Truett explained. “And you get to see a lot of airplanes. It’s just pilots getting together for a good time and good food.”

You can find out more, including the club’s schedule for the rest of the year, at SouthCarolinaBreakfastClub.com.