2025 marks 80 years since the official end of World War II. There are of course, many factors that brought the war to a close, but two things are often credited as ‘secret weapons’ that led the Allied powers to victory: one is codebreaking, while the other is radar technology.

Radar, which stands for Radio Detection and Ranging, is essentially ‘reading’ or identifying objects through radio waves that bounce off those objects and return to a receiver. By measuring the time it takes for reflected waves to return, radar systems can determine an object’s distance and velocity.

The development of radar during World War II

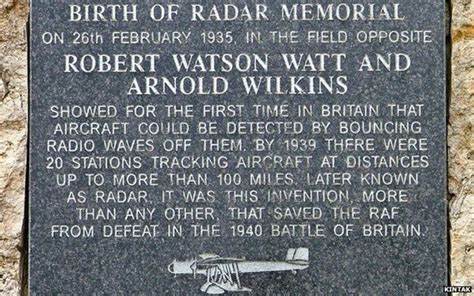

The study and exploration of radar began in the late 1880s, when German physicist Heinrich Hertz discovered that radio waves were reflected by metallic objects.

However, developing practical radar systems for military applications was not achieved until February 26, 1935, when Scottish physicist and radio engineer Sir Robert Watson-Watt demonstrated how radio waves could be used to detect aircraft.

Watson-Watt demonstrated the first practical radio system for detecting aircraft to a British Air Ministry (AM) committee. The Air Ministry was impressed with the technology, and in April 1935, Watson-Watt received a patent for the system and funding for further development.

In late 1939, the opening of higher frequencies to radar was discovered by British physicists at the University of Birmingham. Essentially, this enables radar to detect with better accuracy at shorter wavelengths.

Between 1940-1945, more than 100 different radar systems were developed at the newly-formed Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Radiation Laboratory at Cambridge. The laboratory, then nicknamed the ‘Rad Lab’, became a pivotal research center and played a crucial role in the development of radar technology during World War II.

Why didn’t the Germans develop radar technology during World War II?

It may seem ironic that it was a German physicist who first discovered radio waves reflected by metallic objects, yet radar technology was not heavily deployed or developed by the Nazis as part of their arsenal for World War II.

According to an article by Stanford tech publication Rewired, the Germans grew complacent with their initial radar innovations early on in the war and consistently lagged behind the Allied forces in the development of radar technology.

Instead, German resources were focused on other technologies and tactics, such as improving the Luftwaffe. Germany’s total wartime expenditures from 1939-1945 was USD 270 Billion, the majority of which was spent on improving the Nazi air fleet, such as the Messerschmitt Me 262, known as the world’s first operational jet fighter.

The Dowding System

One of Britain’s most significant victories during World War II was The Battle of Britain, which saw the Royal Air Force (RAF) successfully defend its airspace against the German Luftwaffe between July and October 1940.

The battle was the first major campaign fought solely in the air, and was a key turning point during World War II. By successfully defending British airspace, the RAF prevented Germany from Hitler’s planned invasion of Britain. According to the RAF, the victory provided a solidified Allied resistance against the Nazi onslaught, and provided a much-needed morale boost, proving that the Axis powers were not unstoppable.

British Air Chief Marshal Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding was the head of Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain.

According to the International Churchill Society, Dowding and a number of British scientists briefed Churchill on RDF, the British abbreviation for Range and Direction Finding, also known as radar. Churchill then recognized that Robert Watson-Watt had the foresight to apply the concept of radar to a military system.

The society says that Watson-Watt’s scientific contribution of RDF, or radar, was a major factor in winning the Battle of Britain.

With radar technology in place, Dowding developed an air defence network that had a clearly defined chain of command, enabling control of both the flow of intelligence on incoming raids and the communication of orders. According to the Imperial War Museums, the system brought together technology, ground defences and fighter aircraft into a unified system of defence.

Of his strategy of air defense, Dowding said: “The Germans were aimed to facilitate an amphibious landing across the Channel, to invade this country. Mine was the purely defensive role of trying to stop the possibility of an invasion, and thus give this country a breathing spell. I had to do that by denying them control of the air.”

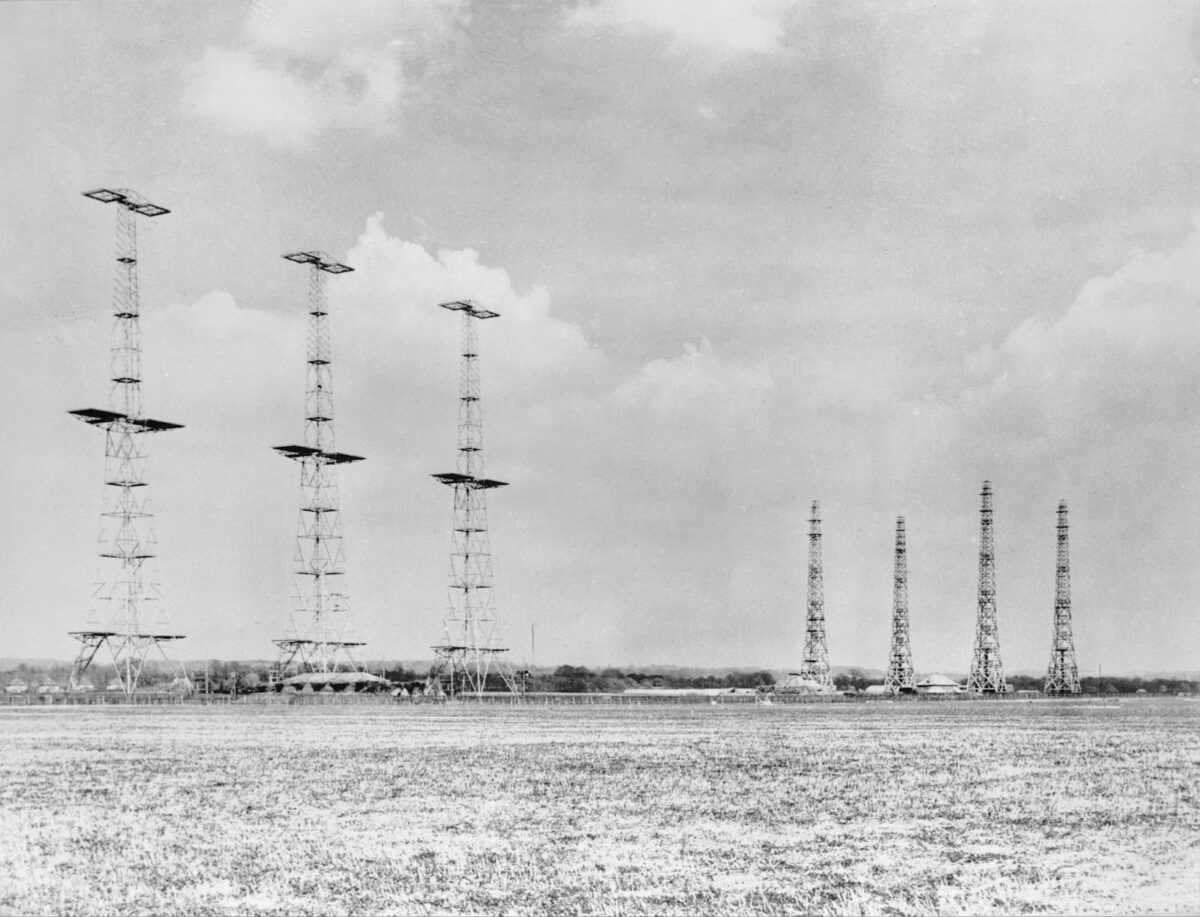

The Chain Home early warning radar system

Radar gave early warning of approaching raids, and Chain Home, codenamed ‘CH’, played a crucial role in defending British skies.

Chain Home’s technical name was AMES (Air Ministry Experimental Station). It consisted of a network of radar stations, spanning the east coast of England. Chain Home was operational 24/7, providing comprehensive detection.

The system was able to warn the RAF about incoming Luftwaffe attacks, contributing to the resistance to, and eventual defeat of, Nazi Germany.

A 2019 case study on Chain Home by the National Defense University Press said that early versions of the system were unable to detect low-flying aircraft. The original system only detected aircraft between 25,000 and 1,000 feet above ground level, creating the potential for German aircraft to evade detection.

To resolve this issue, the RAF designed Chain Home Low, a series of shorter portable towers that could detect aircraft flying at 500 feet.

Why didn’t the Germans just target Chain Home?

In the second volume of his 1951 book, The Second World War: Their Finest Hour, Churchill wrote: “Radar was still in its infancy, but it gave warning of raids approaching our coast, and the observers, with field-glasses and portable telephones, were our main source of information about raiders flying overland,”

If radar was the British / Allied’s main source warning from outside attacks, why didn’t the German Nazis simply destroy the Chain Home stations that surrounded the coast of Britain?

It’s not that the Germans never tried to target Chain Home. They were able to, but underestimated the impact of the destruction of these radar towers.

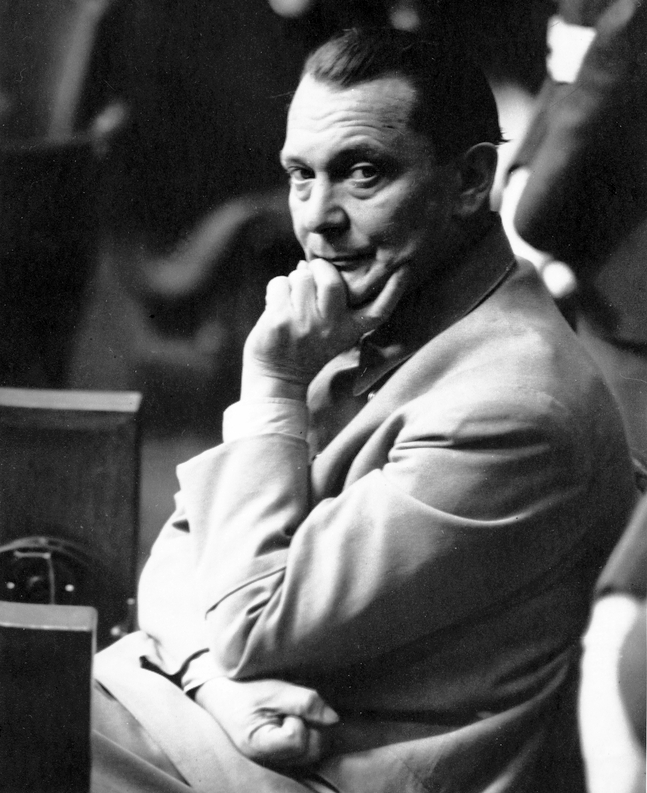

Reichsmarschall Hermann Wilhelm Göring, the second most powerful official in Nazi Germany, was one of those who believed that destroying Chain Home was not worth the effort.

A report published by the RAF said that German bombers targeted radar and sector stations but by August 1940, Göring, believing these attacks ineffective, decided to concentrate Luftwaffe efforts on the bombing of British cities.

Göring’s underestimation of the radar stations enabled the RAF to retain the advantage in the air.

According to RAF reports, in August 1940 Göring said: “It is doubtful whether there is any point in continuing attacks on radar sites, in view of the fact that not one of those attacked so far has been put out of action.”

The Battle of Midway

Using radar as an advantage also paved the way for the Americans’ victory over the Japanese Imperial Army during the Battle of Midway.

The Battle of Midway was a pivotal naval battle that took place on June 4-7, 1942, six months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Midway Islands / Atoll are located in the North Pacific Ocean, specifically in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. It is roughly equidistant between North America and Asia. Much like the Battle of Britain, the US’ victory in Midway halted the growth of Japan’s dominance in the Pacific, and placed the US in a position to put an end to the Japanese empire’s years-long invasion of the Pacific and Southeast Asia.

Although it is considered a naval battle, Midway was fought mostly using aerial combat. Land-based radar placed around Midway spotted inbound Japanese planes long before they reached the islands.

The National Museum of the Pacific War reported that Japanese ships were not equipped with radar, instead relying on their scout planes for information on the whereabouts of US forces. Delays in launching these scouts meant that the Japanese were unaware of how close the Americans were, until it was too late.

“The Japanese had just lost nearly half of their carrier force in the battle and were forced to turn back from their objective. The balance of power in the Pacific began to shift, and the Americans started launching their own offensives against Japan,” the National Museum of the Pacific War reported.

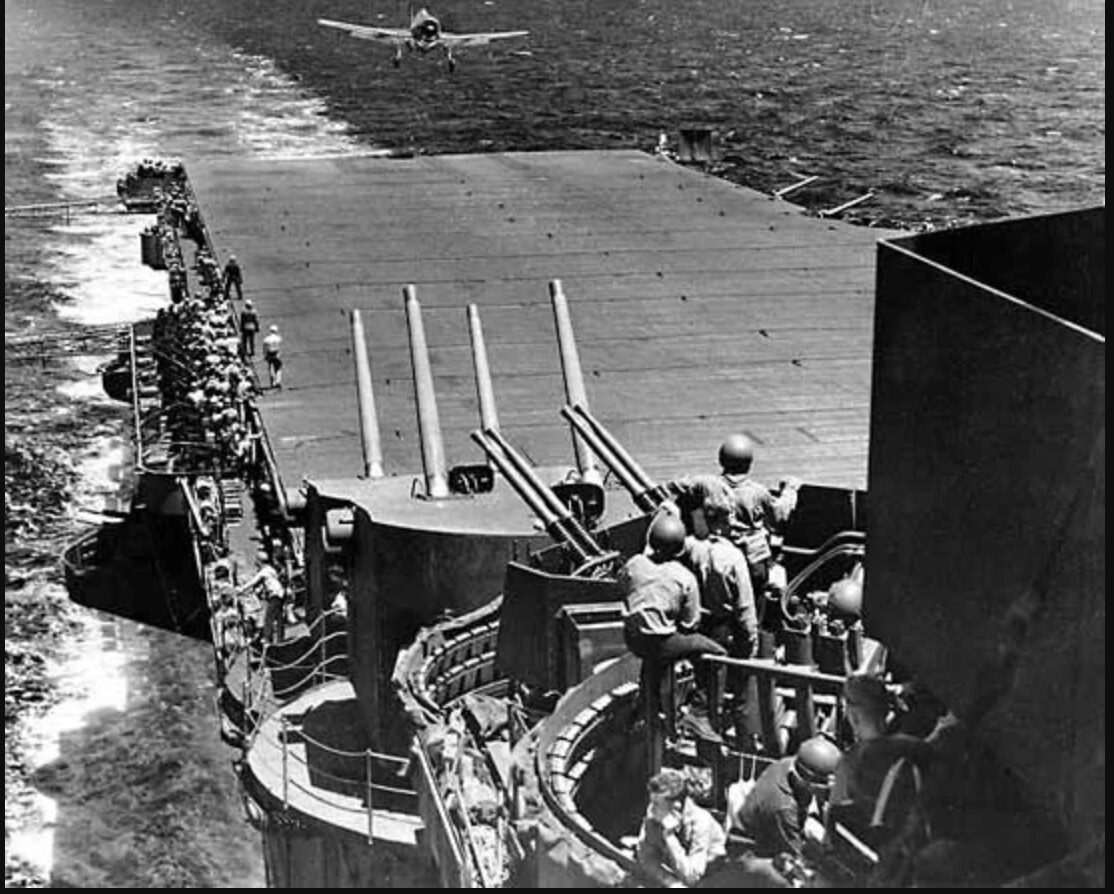

Battle of the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea was a major naval battle that occurred on June 19-20, 1944. The combat took place in the Marianas, a 684-kilometer long chain of 14 islands. Less than 500 kilometers to the Marianas’ north is the Japanese base of Iwo Jima. To the Marianas’ south was the Japanese-occupied Caroline Islands.

The battle, which had a decisive victory outcome for the US, was a crucial point when US forces began their advance towards the Japanese homeland and the Pacific.

Famously, the battle is also known as the ‘Great Marianas Turkey Shoot’, a nickname coined by US aviators due to the severely disproportional loss ratio inflicted upon Japanese aircraft by American pilots and anti-aircraft gunners.

There were a number of factors that led to the decisive victory of the Americans, such as superior US pilot training, advanced anti-aircraft technology, and having more aircraft than the Japanese Imperial Army.

However, it was mainly a combination of breaking the Japanese naval code and employing advanced radar technology that paved the way to victory for the Americans.

Japanese raids and attacks were intercepted in time because of radar detection. The US were prepared for these ‘surprise’ raids, which resulted in Japanese forces losing 476 aircraft, 13 submarines, five destroyers, two oil tankers and three aircraft carriers.

In comparison, the US Navy lost only 130 aircraft, and retained all naval vessels.

Watson-Watts’ legacy

Sir Robert Alexander Watson-Watt died on December 5, 1973, almost 30 years after his scientific discovery led to the triumph of Allied powers.

German ace pilot General Adolf Galland called radar Britain’s “extraordinary advantage”.

“From the very beginning, the British had an extraordinary advantage which we could never overcome throughout the war – radar and fighter control…The British fighter was guided all the way from takeoff to his correct position for an attack on the German formations. We had nothing of the kind,” Galland said.

Today, radar is used throughout our everyday lives: automatic doors on buildings, detecting private vehicles that go over speed limits, weather forecasting, and so on. 80 years on, not many people realize that common and routine tasks are made possible by what was originally, in military terms, an extraordinary advantage.