In an age when US-based company Boom Supersonic has recently sent its X-1 experimental aircraft beyond the sound barrier for the first time (January 28, 2025), supersonic air travel is back on the agenda and grabbing headlines. Yet, while the era of the Concorde, the only commercial production aircraft to have regularly transported fare-paying passengers beyond Mach One, may have ended over two decades ago, the aviation industry is once again looking to the sound barrier as a target for its next endeavors.

However, the Concorde, along with countless other military aircraft of various sizes and descriptions, could never have made that leap beyond Mach One, the official speed at which an aircraft is traveling faster than the speed of sound, without the bravery and spirit of adventure of one pilot and his unwavering passion for aviation.

That pilot was Charles Elwood Yeager (1923-2020), more commonly known as ‘Chuck’ Yeager. During his lifetime, Yeager transformed from a quiet schoolboy growing up in rural West Virginia into one of the most famous pilots in aviation history.

Yeager’s list of achievements in a flying career that spanned several decades is remarkable in itself. But his one crowning achievement came in 1947, in a rocket-powered bullet-shaped aircraft named after his wife, when he became the first human ever recorded to travel beyond the speed of sound.

AeroTime looks back at Chuck Yeager’s life and career, his major career accomplishments, and how he became the fastest man to travel by air at a time when such an achievement seemed little more than an impossible dream.

Background

Yeager was born on February 13, 1923, into a farming family, and was raised in the rural town of Hamlin, West Virginia. One of five siblings, Yeager would attend the local high school, where he became a keen athlete. His first taste of the US military would come in his teenage years when Yeager attended a Citizens Military Training Camp at Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana during the summers of 1939 and 1940.

In February 1945, at the age of just 22, Yeager married Glennis Dickhouse. The couple went on to have four children together.

Early flying career and WW2

In September 1941, with the Second World War already underway in Europe, though the US was yet to become embroiled in the conflict, Yeager enlisted as a private in the US Army Air Force (USAAF). Aged just 18 and still too young to be considered for flight training (something that had been of particular interest to Yeager in his younger years), he settled for starting his military career as a mechanic, based at George Air Force Base in Victorville in the Californian desert.

However, Yeager’s career path and life course would soon be altered when the US entered the war in 1941, just three months after he had enlisted. Having previously applied for flight training, Yeager would later be accepted and begin training to become a USAAF pilot in September 1942. Upon receiving his wings and graduating from flight school in 1943, he initially trained to become a fighter pilot with the 357th Fighter Group based in Nevada. Having successfully qualified to fly aircraft in aerial combat missions, Yeager, along with his pilot cohort, was immediately shipped overseas to face the war head-on as combat flyers.

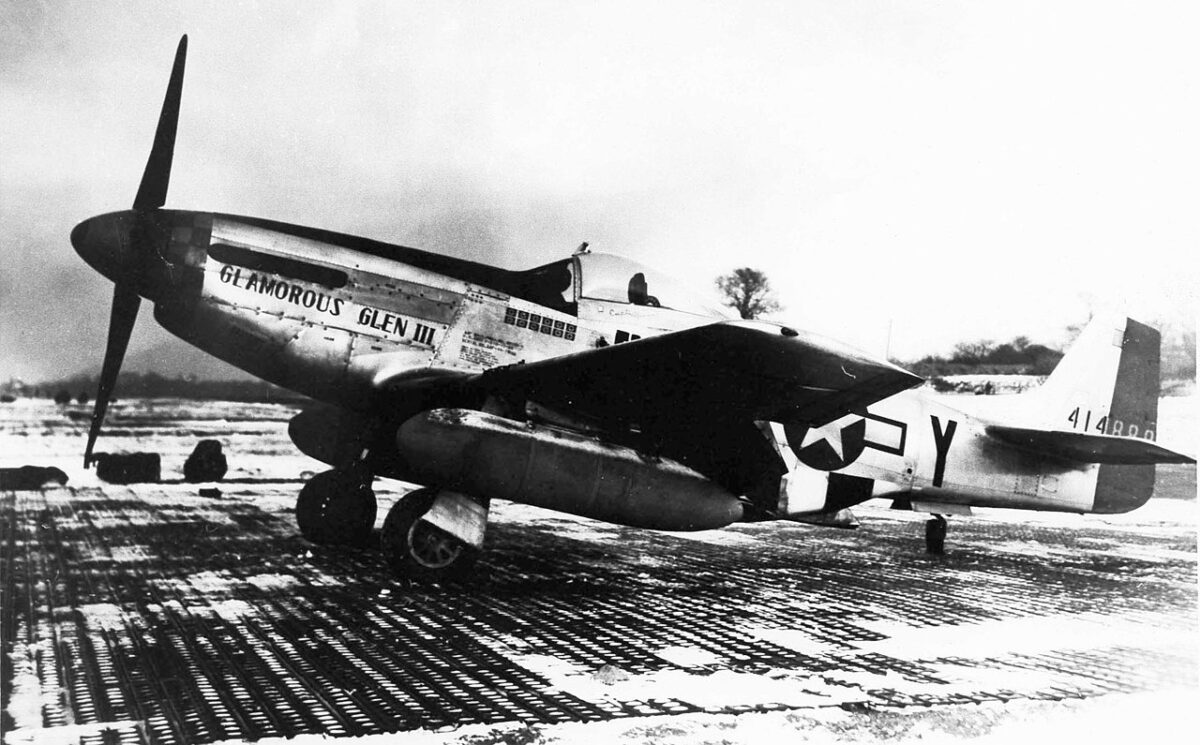

Yeager would be deployed to one of the most active theaters of war at that time – the Western Front in Europe, repelling the Nazi advance across the continent. Holding the rank of Flight Officer in the USAAF, Yeager flew the legendary P-51 Mustang single-engine fighter aircraft in numerous dogfights, often over enemy lines. Yeager would be based at RAF Leiston in the East of England, an airfield located close to the coastline and a convenient location for battle-damaged allied aircraft to land back at after heading back across the North Sea from conflict zones. Yeager flew his P-51 with the 363rd Fighter Squadron of the USAAF. He nicknamed the aircraft ‘Glamourous Glen’ after his then-girlfriend, and later wife, Glennis.

In March 1945, on his eighth mission, Yeager survived being shot down over France. He managed to escape to neutral Spain with the assistance of the French Resistance. During the several weeks he spent in their company, Yeager assisted the Resistance in the construction of explosives, a skill he learned from his father growing up back in West Virginia. He was eventually repatriated back to England in May 1944, and upon his return, he was awarded the Bronze Star for helping a fellow US airman escape over the Pyrenees mountain range to Spain.

A USAAF rule prohibited airmen who had been shot down over enemy lines from returning to fly combat sorties over enemy territory. Nevertheless, Yeager remonstrated this point with Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower himself. Following D-Day, as the war began to tail off, Yeager returned to fly combat missions, as Eisenhower yielded to Yaeger’s demands. One notable shootdown accredited to Yeager was one of history’s very first air-to-air victories against a jet-powered fighter aircraft. Yeager managed to catch a German Messerschmitt 262 just as it approached to land, shooting it down in the process.

Before the end of WW2 was officially declared, Yeager was promoted to the rank of captain before the end of his tour. He flew his 61st and final combat mission on January 15, 1945, and subsequently returned to the United States in early February 1945. Across his numerous missions, Yeager was credited with shooting down an impressive 11.5 enemy aircraft (the half credit is from a second pilot assisting him in a single shootdown). Notably, on October 12, 1944, Yeager was awarded the accolade of ‘Ace in a Day’ by the USAAF, credited with the shooting down of five enemy aircraft in one mission.

Post-war test flying career

Following the end of WW2, and with hostilities over, as an ‘evader’ – an airman who had evaded enemy capture after being shot down – Yeager was afforded the privilege of his choice of next deployment. Having just married and with his new wife pregnant, Yaeger elected to be based at Wright Field, an airbase in West Virginia close to where he was living once more.

With his experience as an aircraft mechanic, along with his impressive war record and the number of flight hours he had amassed flying combat missions in Europe, Yeager became a test pilot tasked with flying recently repaired aircraft. Taking up this position brought Yeager to the attention of the US military’s Aeronautical Systems Flight Test Division.

Yeager would subsequently be selected to undertake training at the USAAF Air Command Flight Performance School, following which he would be stationed at the Muroc Army Airfield in West Virginia, now more commonly known as Edwards Air Force Base, the current home of ‘Air Force One’.

Around this time, serendipitously for Yeager, US aircraft manufacturer Bell Aircraft Corporation was busy designing what they hoped would become the world’s first jet-powered aircraft capable of breaking the sound barrier and flying supersonically – an aviation milestone yet untouched by human engineering.

Yeager was selected as one of just a handful of test pilots for the supersonic flight project. He flew countless test missions onboard various Bell-designed aircraft between 1945 and 1947, becoming familiar with their handling capabilities but also their vulnerabilities – what pilots at the time would refer to as ‘Gotchas’.

Introducing the Bell X-1

According to the US National Air and Space Museum, the Bell XS-1 had been developed as part of a cooperative program initiated in 1944 by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), NASA’s predecessor, and the USAAF, later to become the US Air Force (USAF). The program’s mission was to develop a special manned transonic and supersonic research aircraft.

Breaking the sound barrier was a feat long thought impossible by many, with engineers and scientists struggling to find solutions to the myriad complexities presented by an aircraft flying at such huge speeds. These would include but were certainly not limited to, the immense aerodynamic forces and stresses imposed on the airframe.

On March 16, 1945, the Army Air Technical Service Command awarded a contract to the Bell Aircraft Corporation of Buffalo, New York, to develop three transonic and supersonic research aircraft. The Army assigned the aircraft developed under the contract as the XS-1, standing for Experimental Sonic, although this would later be renamed more simply as the Bell X-1. In all, Bell Aircraft built three rocket-powered X-1 aircraft – small, lightweight, and noticeably bullet-shaped.

The X-1 aircraft was constructed from high-strength aluminum, with propellant tanks fabricated from steel. Yet, despite its sleek lines (designed to resemble the bullet from a .50-caliber machine gun), the aircraft contained a huge amount of equipment. Inside the aircraft were two rocket propellant tanks, twelve nitrogen spheres for fuel and cabin pressurization, the pilot’s pressurized cockpit, three pressure regulators, a retractable landing gear, the wing spar structure, a 6.000-pound-thrust rocket engine, and more than five hundred pounds of special flight-test instrumentation.

Through their research, engineers at Bell Aircraft discovered that bullets could maintain stability at supersonic speeds due to their shape, leading them to design the fuselage of the X-1 along similar lines. The aircraft also featured a cigar-shaped body paired with a set of thin, straight wings. These helped to minimize drag and ensure aerodynamic efficiency at high speeds. This streamlined design helped mitigate the effects of shock waves generated by the aircraft traversing through the sound barrier.

The rocket engine was specifically designed to produce short bursts of intense power, perfect for taking the aircraft through the sound barrier. However, with the engine using a highly volatile cocktail of liquid oxygen and alcohol as propellants, every flight was a risk, requiring extreme concentration and expert handling by the pilot.

Though originally designed for conventional ground take-offs, the X-1 aircraft was subsequently air-launched from the underbellies of Boeing B-29 or B-50 Superfortress aircraft. The performance penalties and safety hazards associated with operating rocket-propelled aircraft from the ground caused mission planners to resort to air-launching instead. The engines used in the development of the Bell X-1 would later influence the design of spacecraft propulsion systems and advanced military, expertise that is still in use today.

Breaking the sound barrier

Having built its X-1, the aircraft that the company hoped would become the first to break the sound barrier, Bell Aircraft now needed someone to fly it. However, the company’s plan would come temporarily unstuck when Bell’s lead test pilot, Chalmers ‘Slick’ Goodlin, demanded a one-off payment of $150,000 (worth around $2.2 million in 2025) to fly the machine and take it supersonic. Little did Goodlin know that by making such demands, he was passing up the chance of a lifetime to have his name forever recorded in aviation history.

With its budget already limited, Bell turned to its next candidate for the job. This was Yeager, who leaped at the opportunity to fly faster than anyone had ever flown before, such was his undiminished appetite for adventure.

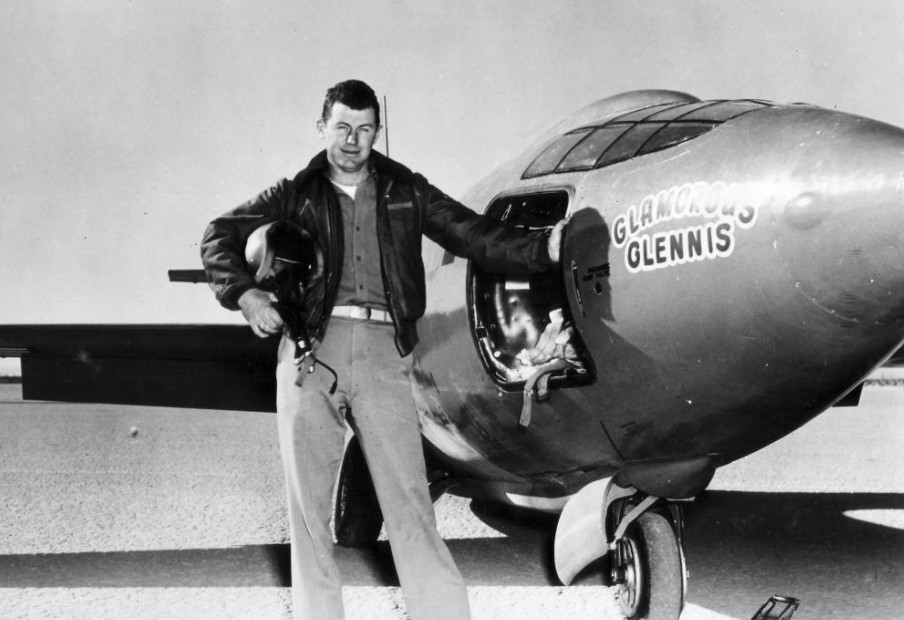

On October 14, 1947, Bell X-1 aircraft #1, piloted by Yeager who, continuing a lifelong theme, had nicknamed the aircraft ‘Glamorous Glennis’ after his wife, became the first airplane to fly faster than the speed of sound (also known as Mach One). Air-launched from the bomb bay of a Boeing B-29 bomber after a 30-minute climb to 20,000 feet (6,000m) above Rogers Dry Lake in the southern California desert, the X-1 used its rocket engine to climb up to its test altitude of 42,000 feet (13,700m) and began its test run.

On this, the ninth powered flight of the X-1, the Mach meter onboard jumped from Mach .965 to Mach 1.06, faster than the speed of sound. The experimental aircraft reached a staggering 700 mph (1,127 kph) during the test flight, shattering the sound barrier with an iconic sonic boom that could be heard by the engineers back on the ground.

It was later reported that the transition to supersonic flight was remarkably uneventful for the X-1. After flying supersonically under power from its rocket engine for 20 seconds, Yeager cut the power and glided down to the lakebed for a safe landing. Without braking equipment onboard, the aircraft traveled for over two miles before finally coming to a halt. The world’s first piloted supersonic flight lasted 14 minutes, from release from the B-29 to landing back in the desert.

In total, the Bell X-1 flew 78 times during its test program, often with Yeager at the controls. It managed to fly as fast as Mach 1.45 and as high as 71,900 feet (21,900m) during those flights. Additionally, the X-1 program gathered crucial flight data about transonic and supersonic flight for the NACA/NASA program of aircraft development, which would lead to a series of ‘X’ experimental piloted and unpiloted projects that explore and expand the possible envelopes of flight – projects that continue today.

At the time, many feared that supersonic flight was impossible because of an ‘invisible barrier’ that may destroy aircraft should they pass through it at supersonic speeds. However, Yeager’s exploits had put such thoughts to rest and opened the world’s eyes to a host of new possibilities. As Yeager later stated, “I realized that the mission had to end in a letdown because the real barrier wasn’t in the sky but in our knowledge and experience of supersonic flight.”

What came next for Yeager?

Having become the poster boy for global aviation achievement and won various awards for his outstanding accomplishment in breaking the sound barrier, Yeager went on to break several other speed and altitude records in the following years, while working on various high-profile (and some more secretive) NACA missions. In 1953, Yeager flew a new experimental aircraft, the X-1A, in a series of test flights dubbed ‘Operation NACA Weep’. He set a new speed record of Mach 2.44 in it on December 12, 1953, becoming the fastest flight ever flown by humans at that time.

The new record flight, however, did not entirely go to plan. Shortly after reaching Mach 2.44, Yeager lost control of the X-1A at about 80,000 ft (24,000m) due to a phenomenon known as inertia coupling, little understood by aeronautical engineers at the time. With the aircraft simultaneously rolling, pitching, and yawing out of control, Yeager dropped 51,000 ft (16,000m) in less than a minute before regaining control at around 29,000 ft (8,800m). He then managed to land without further incident.

In 1962, he became the first commandant of the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School, a US military institution tasked to train and produce astronauts for the Gemini, Apollo, and Mercury space programs, as well as the USAF itself. However, with combat flying still in his blood, Yeager would later return to the USAF as a fighter pilot in the rank of Squadron Leader, operating from bases in West Germany, France, Spain, and California. Later, during the Vietnam War, the USAF tasked Yeager to train its bomber pilots and also flew 127 air-support missions himself in theater.

In the later part of his career with the USAF, Yeager was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General. After 34 years of service with the USAF, Yeager formally retired from the Air Force on March 1, 1975 – fifty years ago in March 2025.

Post-retirement life

Following his retirement from the USAF in 1975, as Brigadier General Charles Yeager, he continued to serve the USAF as a consultant test pilot. He also served on multiple overseas defense missions in Europe and South Asia for the USAF in a consultancy pilot role.

On October 14, 1997, at the age of 89 and to mark the 50th anniversary of his legendary supersonic flight in the Bell X-1, Yeager made his last ever supersonic flight, this time onboard a USAF McDonnell Douglas F-15D. Yeager, acting as co-pilot to Captain David Vincent of the USAF, flew the F-15D (dubbed ‘Glamorous Glennis III’ for the special occasion) at over Mach One from Nellis Air Force Base in California. His wife Glennis died in 1990, predeceasing Yeager by 30 years.

Having successfully broken the sound barrier for one last time, Yeager gave a speech in which he stated, “All that I am, I owe to the Air Force“. He died on December 7, 2020, at the age of 97 in a hospital in Los Angeles. However, as a WW2 hero, flying ace, long-serving military aviator, and above all, the first pilot to break the sound barrier, his enduring legacy, as well as his rightful place in the aviation history books, was assured.

Awards and legacy

Throughout his life, Yeager flew more than 360 different types of aircraft over a 70-year flying career. However, during his lifetime, and indeed since, Yeager accumulated almost as many awards as he did flight hours during his flying days.

In 1966, Yeager was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame. In 1973, he became the first pilot to be inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame, arguably aviation’s highest honor. In 1975, he received the Silver Medal from the US Congress for “contributing immeasurably to aerospace science by risking his life in piloting the X-1 research airplane faster than the speed of sound”.

Yeager later received the Congressional Silver Medal from President Gerald Ford in 1976. In 1981, he was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame, and four years later, in 1985, Yeager was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan. He was inducted into the Aerospace Walk of Honor in 1990, and in 2003, the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC ranked him as the fifth greatest pilot of all time. Lastly, Charleston Airport, located near Yeager’s hometown in West Virginia, was renamed in his honor in 1985 as West Virginia International Yeager Airport (CRW).

Through his endeavors with NACA in the 1940s, and his experiences flying the Bell X-1, Yeager paved the way for the future of supersonic flight. With his seemingly boundless bravery, excellent flying skills, and unsurpassed passion for aviation helped to break the sound barrier, along with the expertise of countless designers, engineers, and others, Yeager made it happen.

The lucky few to have flown supersonically since, including military and space aviators, as well as the thousands of passengers who got to fly on Concorde during its service life, can all proudly wear the badge to say that they have broken the sound barrier. For the rest of us, our hopes now lie with such companies as Boom Supersonic to allow us the opportunity to one day join that elusive club. Until then, we can only imagine how it must feel to travel faster than a bullet and to break the sound barrier at Mach One, strapped to a rocket-powered machine.