BERLIN — The shallow waters of the Baltic Sea have become a secondary arena of confrontation in the larger standoff between the East and the West. Fears of hybrid warfare, coupled with key vulnerabilities on both sides, make this narrow stretch of water one of the key areas to watch as hybrid warfare activities expand and NATO bolsters its eastern flank.

Recent events show just how seriously both sides are taking the challenge.

When two undersea cables were severed in mid-November – one connecting Germany to Finland, and one Lithuania to a Swedish island – Germany’s defense minister was quick to announce that “no one believes that these cables were cut accidentally,” hammering the point home by adding that “we have to assume … it is sabotage.”

Soon after the cables were cut, armed vessels from several Baltic Sea states, including Denmark, Sweden and Germany, approached a Chinese ship that they suspected of having been responsible for the rupture, the Yi Peng 3, making its way toward the Atlantic. Visible damage on the ship’s anchor and hull, seen by journalists from a Danish state broadcaster, suggested it may have dragged its anchor across the sea floor in an effort to cause damage.

Satellite-based ship tracking data implies a tense standoff with the ship stopped just a short distance outside of Danish territorial waters and being watched over by armed European vessels. A Russian warship was keeping nearby, spotted on satellite imagery. The ship’s owner, China-based Ningbo Yipeng Shipping, told the Financial Times that “the government has asked the company to cooperate with the investigation.”

It wasn’t the first time that undersea infrastructure in the Baltic Sea mysteriously and violently disconnected. It wasn’t even the first time that a Chinese cargo ship had dragged its anchor across a cable connecting two NATO states and caused considerable damage in doing so. In October 2023, the Newnew Polar Bear damaged a gas pipeline and data cables in the same manner.

And in September 2022, months after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Nord Stream gas pipelines connecting Russia to Germany exploded, leaving a gaping hole and taking them out of commission. While much blame was initially heaped on Russia, the Kremlin has denied any wrongdoing, and additional evidence has emerged since that complicates the picture. A perpetrator has not been publicly identified, although German authorities have issued an arrest warrant for a Ukrainian man in connection with the incident.

So, what is going on in the Baltic Sea, and why is it suddenly so important?

A NATO ‘lake’?

With the recent accession of Finland and Sweden – two previously longtime neutral states – to NATO, many Western observers triumphantly declared the 386,000 square kilometer sea a “NATO lake.” Russia, whose empire once controlled roughly half the coastline here, now holds on to only about 700 kilometers around Saint Petersburg and its Kaliningrad exclave wedged between Lithuania and Poland. Both are incredibly valuable to Moscow: Kaliningrad is heavily militarized and serves as the headquarters of the Baltic fleet, while Saint Petersburg is one of the region’s most important financial centers and plays a major role in Russian foreign trade.

Kaliningrad is also Russia’s only year-round ice-free port in the Baltic. And the territory’s forward position much closer to Western Europe makes it prime real estate for stationing bombers and missiles, according to Moscow’s calculus.

For Russia, as for the other states sharing the Baltic coastline, the sea and its narrow connection to the open Atlantic through the Danish Straits is a crucial link to global trade and commerce. Things get crowded there: Around 2,000 ships are in the Baltic at any given time, and the trade volume amounts to about 15% of the global total, according to the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission HELCOM.

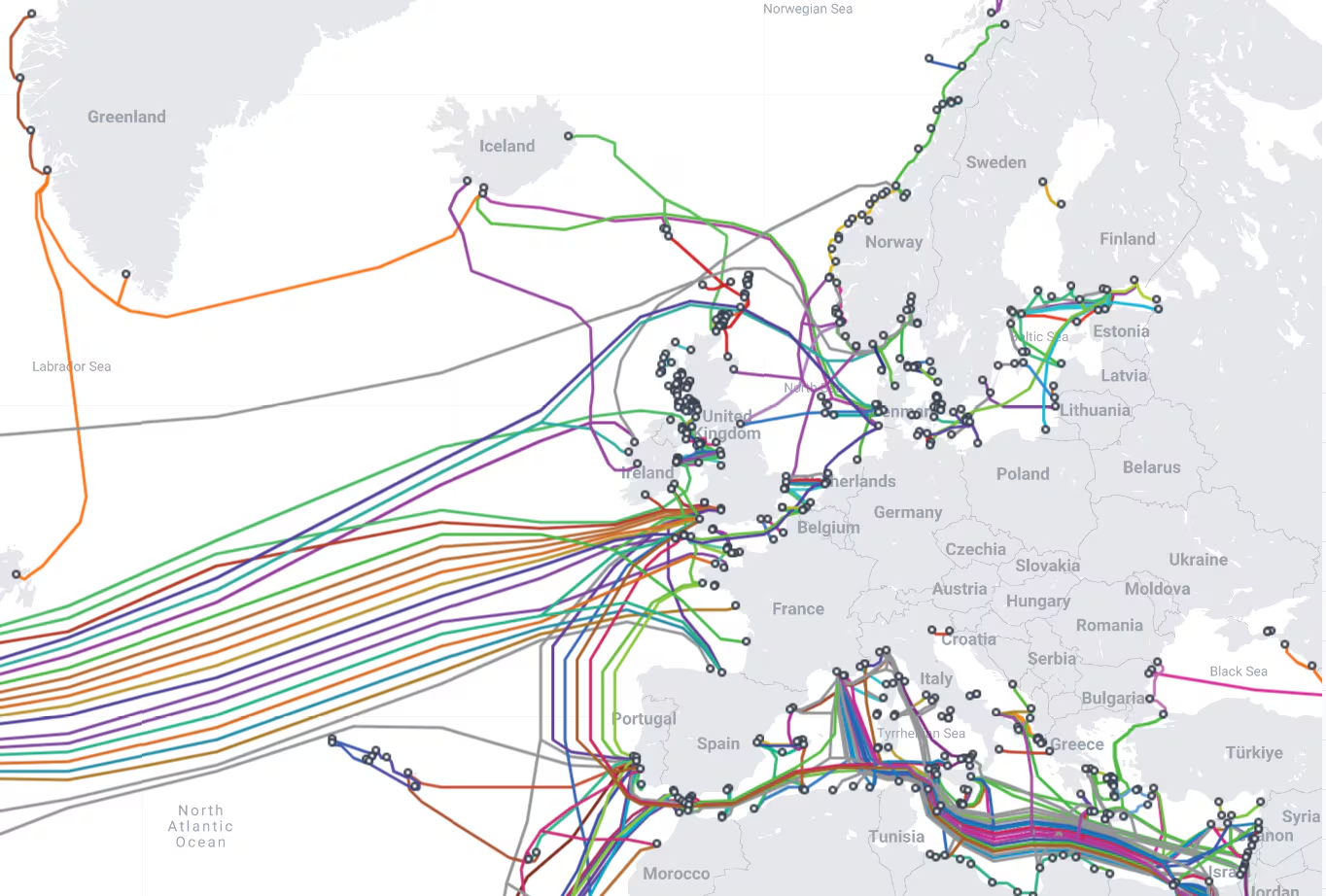

It’s not just what’s on the water but what lies under it that has attracted attention – wanted and unwanted. Beneath the waves stretch dozens of cables transporting power and information between the tightly interconnected European countries on either side of the straits. These pieces of undersea infrastructure crisscross through national and international waters, under shipping lanes and across the exit from the Gulf of Finland, which harbors Saint Petersburg. They are joined by other maritime infrastructure usually found closer to the shore, like liquefied natural gas terminals taking deliveries of gas from countries that Europe has better relations with than Russia, and wind farms that were developed to bolster Europe’s energy independence.

The cutting of undersea cables is not a new hybrid warfare tactic. During World War I, both the British and German navies severed the opposing side’s underwater telegraph lines. The idea of hybrid warfare likely has become attractive for Russia due to the military imbalance with the West: Moscow avoids engaging in outright war by employing plausible deniability while still having the potential to undermine Western infrastructure, resolve and cohesion, explained Sebastian Bruns, a senior researcher at the Kiel, Germany-based Center for Maritime Strategy and Security.

“With thousands of kilometers of cables spread across the world’s oceans, it is practically impossible to ‘protect’ them all in an efficient way,” said Basil Germond, a professor of international relations at Lancaster University who researches naval affairs and maritime security. Instead, redundancy and deterrence must be employed. If a network is redundant enough, there will be no significant impact from an attack unless it is large-scale and coordinated, he argued.

Military posturing

The crowdedness and strategic importance of the Baltic to its neighbors means that it has played a central role in these countries’ defense policies. For Russia, access to the Baltic Sea is vital to keep Kaliningrad supplied, as the exclave lacks a direct land connection to Russia and is surrounded by NATO members. To others, like Sweden, it presents the country’s longest frontier and one that is remarkably tough to guard: With archipelagos, bays and sounds, there are plenty of places for unwelcome guests to hide, which led to repeated submarine hunts during the Cold War years.

As a result, Sweden and other Baltic states have developed uniquely adapted navies and military doctrines for the Baltic littoral environment. The Swedish navy operates a fleet of five submarines designed for brown-water operations near land – and is constructing two more – in contrast to the blue-water, deep-sea navies of other NATO states, and a set of seven minesweepers and other boats designed to operate close to shore.

The Baltic Sea is a unique environment, boasting an average depth of just around 55 meters. It is also considered brackish water (an in-between level between salt- and freshwater) due to the many rivers that empty into it. Layers of varying salinity provide ideal conditions for submarines to hide, especially the smaller ones capable of operating in the Baltic in the first place.

States around the Baltic Sea have been some of Ukraine’s most ardent supporters, given their own proximity to Russia. Particularly the Baltic nations have sent outsized contributions to Kyiv’s defensive war effort: Estonia and Lithuania gave 1.8% of their GDP to Ukraine and Latvia 1.5%, according to a report by the Wilson Center, a Washington-based think tank.

In September, NATO announced it would open a naval command center for the Baltic Sea in the German coastal city of Rostock to “coordinate naval activities in the region” and provide NATO with a “maritime situation picture in the Baltic Sea region around the clock,” according to the German military. Staff from 11 other alliance countries will be present at the HQ.

Russia decried the move as a violation of an agreement that no NATO forces would be moved to the territory of the former GDR, which the USSR had considered a precondition to agree to German reunification following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the East German government in 1989.

German defense minister Boris Pistorius argued the naval command center was necessary to “ensure that Putin will not have his way,” referring to Russian President Vladmir Putin.

According to experts, the quick response to the most recent case of severed cables shows that European preparation has worked. Efforts led by NATO have focused on better surveillance and operational coordination, said Christian Bueger, author of the book “Understanding Maritime Security” and professor at the University of Copenhagen. The involved governments’ reaction to the Yi Peng 3 incident “clearly indicates that the strategy and coordination on the NATO level work well now,” he said.

Simultaneously, the increased attention has galvanized scrutiny of national and international legal frameworks for protecting undersea infrastructure and interdicting ships. Some countries, such as Belgium, have moved to introduce legislation criminalizing damage to critical infrastructure. On the other side of Europe, Portugal and Italy have led the charge in coordinating with industry and conducting legal reviews on the security of maritime infrastructure, said Bueger.

How is China involved?

The part of the story that continues to perplex analysts is the China connection.

In both recent incidents, it was Chinese civilian vessels that appear to have dragged their heavy anchors along the seafloor for large distances on their way out of Russian waters and toward the open Atlantic, a pattern that has baffled marine experts. It is unlikely such a thing would happen accidentally, most say, and even less likely that it would go unnoticed by the crew for long stretches. Suspicious movement of the vessels near crucial undersea infrastructure and away from typical shipping routes further suggests intentionality rather than accidents.

In both cases last month, the Chinese government rejected any claims that it had been involved. Additionally, Chinese authorities appeared cooperative and, in the case of the damaged gas pipeline and data cables between Estonia and Finland, later even publicly stated that their ship had accidentally caused the damage.

Mao Ning, a spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, said on the more recent incident involving the cables around Estonia, Sweden and Finland that “China maintains communication with relevant parties, including Denmark, through diplomatic channels.” Reporting from governments involved in the investigation seemed to support this and indicate a generally constructive attitude.

What exactly is going on here is hard to say. While China has an interest in undermining the West, broadly speaking, in its quest to replace the United States as the world’s preeminent superpower, it has little reason to be focused on the Baltic Sea in particular. Nor does it have a significant track record of similar actions in parts of the world more relevant to China’s immediate geopolitical ambitions, though it has used some methods that could be considered hybrid tactics in the disputed archipelagos of the South China Sea.

Several experts interviewed for this story said they considered it highly unlikely the Chinese government was directly involved. However, with Chinese shipping companies being among the few that still conduct business with Russia, they said there is a chance of their ships being employed – even unknowingly – for nefarious actions.

Both of the Chinese ships involved in the recent Baltic incidents had fairly close ties to Russia, beyond simply coming from a Russian port when the damage took place. The Economist has previously reported that the Newnew Polar Bear, linked to the damaged pipeline between Estonia and Finland, had a number of ties to Russia, including through its ownership, crew, prior voyages and shipping contracts.

While less is known so far about the 225-meter-long Yi Peng 3, reporting has emerged that suggests similar connections. Erik Kannike, an Estonia-based defense consultant, found that Russian federal port records listed the captain of the ship as being a Russian citizen. He also pointed out that the vessel’s ownership was only transferred to the current company about a month before the incident. The presence of a Russian warship near the site of ongoing investigations further suggests Russian interest in the case.

Among the unresolved questions, one thing is certain: The Baltic Sea has shaped up to be a new frontier in the geopolitical cat-and-mouse game that has engulfed Europe since the escalation of the war in Ukraine.

With surveillance technology still allowing attacks on sea floor infrastructure to go unnoticed, more incidents testing the waters may only be a matter of time.

Linus Höller is a Europe correspondent for Defense News. He covers international security and military developments across the continent. Linus holds a degree in journalism, political science and international studies, and is currently pursuing a master’s in nonproliferation and terrorism studies.