Today’s modern international airport may boast about its range of facilities, its expansive route network served by a range of airlines, or other aspects that make the airport unique among its peers. Consider Singapore-Changi Airport (SIN) with the world’s highest indoor waterfall, or Hong Kong International Airport (HKG) with the first-ever IMAX cinema constructed within an active airport terminal building.

Yet there is only one international airport in the world that can claim to have two human graves embedded within the asphalt surface of its main runway. Savannah-Hilton Head International Airport (SAV), located on the border of the US states of Georgia and South Carolina is that airport, where two gravestones lie within the runway’s surface on which dozens of commercial passenger planes land and take off every day, 365 days a year.

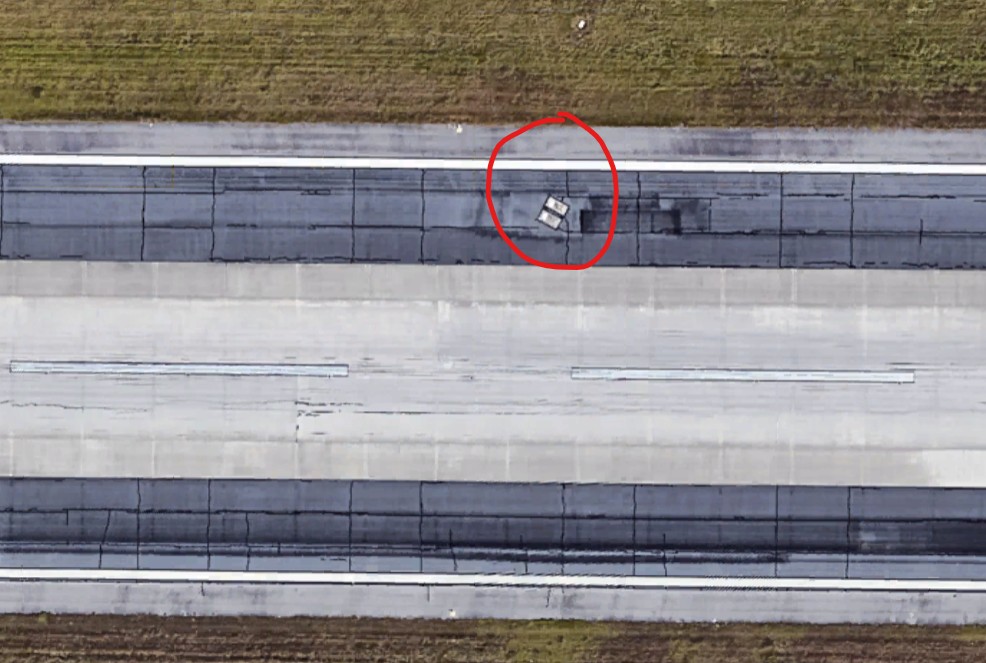

It is highly unlikely that the existence of the two gravestones, lying side-by-side in parallel on the north side of runway 10/28 at the airport comes to the attention of many of the thousands of passengers that pass over them every day. Yet not only is their existence unique among international airports worldwide, but the story of how and why they are there is as poignant as it is intriguing.

AeroTime looks into the history of the graves, the story behind them, and why they continue to lie within a strip of tarmac heavily used by passenger aircraft as they arrive or depart from Savannah.

History of Savannah-Hilton Head Airport

The city of Savannah in the state of Georgia has had an active airfield almost as long as commercial flights have been in existence. The city, separated from the next-door state of South Carolina by the Savannah River, opened its first airfield in 1918 on the southern edges of Daffin Park, with a single east-west runway measuring just 2,500ft long (833m) by 450ft (150m) wide. Aircraft operations continued at Daffin Park until 1930.

Deemed unsuitable to cope with forecast expansion, in 1928 city authorities identified another 730-acre site that could be developed into a municipal airport for the region to take over the duties of Daffin Park. In 1929, the new Savanah Municipal Airport opened for the first time, with the first flights being operated by Eastern Air Express to New York and Miami. The airport assumed the new name of Hunter Field in 1932.

In 1940, the US Army Air Corps (USAAC) proposed a complete takeover of Hunter Field if the US became involved in World War Two. Although commercial airlines continued to land at the airport, a decision was eventually made to construct a second municipal airport for the exclusive use of commercial flights in response to the increased military presence at Hunter Field. The City of Savannah acquired a 600-acre tract in the vicinity of Cherokee Hill, one of the highest elevations in the region, and construction of the new airport began.

However, in 1942, before the completion of the new airfield, the USAAC found it necessary to take over the new facility as well and start additional construction to accommodate their larger aircraft. The new airfield would be named Chatham Field, and the new facility was used until the end of WW2 as a B-24 bomber base and aircrew training facility for both B-24s and other combat aircraft.

In 1948, Chatham Army Airfield as it became known was turned over to the Georgia Air National Guard, and its name was changed once more to Travis Field. With the airport fully adopted by the US armed forces, the original Savannah airport at Hunter Field became surplus to their requirements and was handed back to the City of Savannah. However, just a year later, in 1949, the City of Savannah received a quit claim deed to Travis Field, and in 1950, the city’s main civilian airport returned once more to Travis Field.

With Travis Field now becoming the established airport for Savannah, the construction of a new control tower and passenger terminal began in 1958, with the first six-gate building completed two years later in 1960. As the airport developed with the surge in post-war air travel, the airport continued to develop and grow. In 1983, the airport changed its official name to Savannah International Airport, while in 1994, a newly built 275,000 sq ft (24,750 sq m) terminal building opened with ten aircraft stands, plus new aprons and taxiways.

In 2003, the airport changed its name once again to Savannah-Hilton Head International Airport, realizing that a growing number of passengers were using the airport to access destinations across the border in South Carolina, including the popular coastal resort of Hilton Head Island.

The Dotson family

Around the time that the USAAC adopted Chatham Field as a supplementary airfield in Savannah to the original Hunter Field and began expanding its operations, the US War Department declared a need for additional facilities at the site. A lease was subsequently negotiated between the federal government and the City of Savannah for a further 1,100 acres adjacent to the airport site, still known at that time as Cherokee Hill.

Part of the acquisition of the additional land required by the USAAC included a private family cemetery belonging to the locally-established Dotson family. It was understood that the Dotson family cemetery contained one hundred or more graves at that time. The land had originally been owned by the Dotson family for generations by that point, with a farm having been established on the land by Richard and Catherine Dotson in the 1800s.

Following their deaths later in the 19th century, Richard and Catherine Dotson were buried on the family farm, in a spot that they had selected before they passed away. It then became a family tradition that other members of the family would all be buried near the same spot on the farm.

More about the graves

With the US War Department seeking to expand Chatham Field as the war progressed, the subject of the Dotson family graveyard became an issue. Despite the US government needing the land at Cherokee Hills, US federal law dictated that graves could not be moved unless express consent from the next of kin of the graves’ occupants could be obtained.

Having received an approach from the authorities, the Dotson’s great-grandchildren began negotiations with the Federal Government over the issue but were initially reluctant to agree to any of the graves being moved. To not inhibit the war effort and the development of the airport, the American armed forces said they would pay to move most of the cemetery to a new site. Eventually, a settlement was reached by the respective parties whereby all but four of the Dotson ancestors would be relocated to Bonaventure Cemetery in central Savannah.

However, it was determined by the Dotson family that the graves of Catherine and Richard Dotson had to be left in place, in accordance with their wishes, along with two other much-loved family members, Daniel Hueston and John Dotson. Even when they were advised that a new east-west runway was needed at the airport to handle new larger WW2 aircraft, the Dotson family stood firm – the graves were not to be moved, regardless of the exact location of the new runway.

Therefore, the graves of Richard and Catherine Dotson along with their two beloved relatives, remained undisturbed where they had first been located. Despite the two main gravestones being embedded to the north side of the new 10/28 runway, with the other pair being located in the grass area close by, the graves have laid undisturbed ever since, despite lying beneath the airport’s most active runway.

As passenger aircraft take off and land at the airport nowadays, the two distinct grey rectangular shapes can easily be spotted by passengers as they pass by the final resting place of Richard and Catherine Dotson. Not only do these gravestones commemorate the lives of the original owners of Cherokee Hill, on which Savannah-Hilton Head International Airport was eventually built, but they remain the only graves embedded in an active 9,350-foot runway in the world – a runway that serves thousands of general and commercial aviation movements annually.

The airport today

Today, Savannah-Hilton Head International Airport operates as a busy private and commercial airport, handling 114,986 aircraft movements and 4.1 million passengers in 2024. Currently, all three major US carriers (United Airlines, Delta Air Lines, and American Airlines) serve the airport from various points nationwide, using both mainline and regional aircraft fleets.

The airport also receives regular services from other carriers including Breeze, Allegiant, Southwest Airlines, JetBlue, Avelo Airlines, and Frontier Airlines. In total, 33 destinations are currently served from the airport, although despite its name, there are currently no international flights operated from the airport (as of April 2025).

In November 2024, the airport was voted the #1 airport in the United States by the Condé Nast Traveler magazine Readers’ Choice Awards.

Summary

Notwithstanding the war effort during the 1940s and the need for longer runways to accommodate larger aircraft, it is heartwarming to consider that the wishes of the Dotson family were respected and that Richard and Catherine Dotson have laid undisturbed despite the thundering jets that pass just above them and the requirements of a modern international airport around where they now lay.

So, if you ever find yourself landing or taking off from Savannah-Hilton Head International Airport at any point, do remember to keep a good lookout for the odd-looking and seemingly out-of-place grey rectangles to the northern edge of runway 10/28. At least you now know what they are, why they are there, and the identities and story behind those who lie beneath them.